In the annals of American ingenuity, where the line between breakdown and breakthrough blurs like heat haze over asphalt, Elon Musk has always been less a man than a force. He is a restless voltage arcing through the machinery of progress.

I wanted to write about 2107. What prompted me was a conversation I had with a man who was working in the Fremont factory and recalled seeing Elon sleeping in the factory. “Every morning when I would go to my station on the production line, I would walk past the conference room and see him there, he slept there, he was close to the team.”

One November evening in 2017, as the Bay Area fog clung to the Fremont Factory’s vast halls, that force appeared to flicker low. Jon McNeill, then the company’s president of global sales, pushed open the door to a conference room and found Musk sprawled on the carpet, the lights extinguished. It was moments before an earnings call with Wall Street’s sharp-eyed inquisitors, a ritual as unforgiving as any inquisition. “Hey, pal,” McNeill murmured, easing himself down beside the prostrate form. “We’ve got an earnings call to do.” From the dimness came Musk’s voice, ragged and remote: “I can’t do it.” A half-hour of gentle coaxing followed—McNeill drawing him from a coma-like stupor to a chair, cueing the opening remarks, even covering for him as the questions flew.

When it ended, Musk bolted: “I’ve got to lay down, I’ve got to shut off the lights. I just need some time alone.” This tableau, rendered with unflinching intimacy in Walter Isaacson’s biography, repeated five or six times that autumn, including once when McNeill pitched a website redesign from the very floor beside his boss. It was “production hell,” as Musk would call it—a crucible of sleep-deprived nights in the factory, where he debugged robots at 2 a.m., rewrote code in marathons, and slept amid the whir of assembly lines. Yet from this abyss, as the earnings call unspooled live to the world, emerged not defeat but a torrent of revelation: Elon Musk, sniffling through a cold, his desk a phantom in the Gigafactory’s glare, delivering a monologue that fused raw confession with visionary fire. Here, in the unvarnished transcript of his words, was Musk at his most electric—not the polished oracle of TED stages, but the engineer-prophet, voice cracking with fatigue, mapping the escape from entropy.

Musk began, as he often does, not with platitudes but with the unyielding arithmetic of ascent. “So, sorry, one minute, I have a bit of a cold,” he said at 1:30, his tone a gravelly apology laced with defiance, “so, yes I’m actually — we’re doing this call from the Gigafactory because that’s where the production constraint is for Model 3, the most important thing for the company, and I always move my desk to wherever, well, I don’t really have a desk, actually. I move myself to wherever the biggest problem is in Tesla, so I’m at, I really believe that one should lead from the front lines and that’s why I’m here.”

It was a declaration of method, this nomadic command: the CEO as itinerant troubleshooter, forsaking corner offices for the front lines. From there, he pivoted to milestones, his voice gathering steam like a line accelerating out of stall. “One thing that I thought was really profound was that we surpassed cumulative deliveries of vehicles. We surpassed a 0.25 million cumulative deliveries since the company’s inception and had record Model S and Model X net orders and deliveries last quarter, so things are really going quite well.”

He paused, then drove the point home with the precision of a slide rule: “To put that into perspective, five years ago we had only delivered 2500 cars, so the Tesla fleet has grown by a factor of 100 in five years. I would expect five years from now to be at least an order of magnitude beyond where we are right now and possibly even close to two orders of magnitude.”

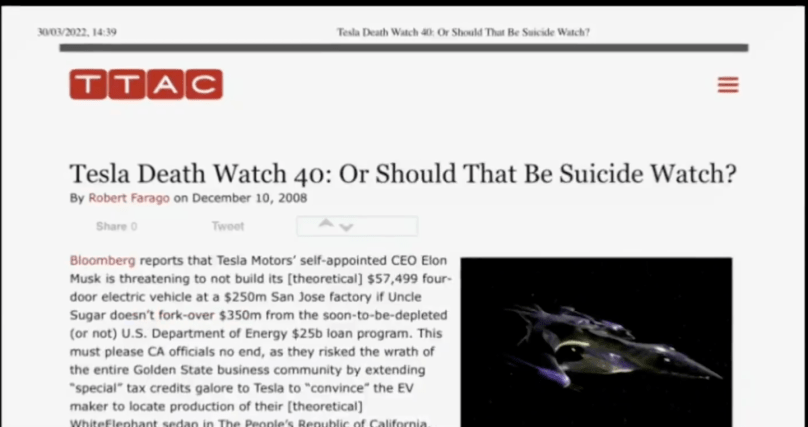

Such projections invited skepticism, a chorus Musk preempted with his trademark wit. “But for the skeptics out there, I’d like to say, ask them which one of you predicted that Tesla would go from 2500 units delivered to 250,000 units delivered now. I suspect the answer is zero. So consider your assumptions for the future and whether they’re valid or perhaps pessimistic.”

It was Musk’s genius in microcosm: not bluster, but a scalpel to complacency, reminding listeners that the doubters’ linear forecasts had already been lapped by reality’s exponential curve. And oh, how he lingered on that curve, dissecting the Model 3 ramp with the tender ferocity of a surgeon in extremis. “For Model 3, we continue to make significant progress each week. We’ve had no problems with our supply chain or any of our production processes. Obviously, there are bottlenecks. There are thousands of processes in creating the Model 3, and we will move as fast as the slowest and least lucky process among those thousands. In fact, there’s 10,000 unique parts, so to be more accurate, there’re tens of thousands of processes necessary to produce the car. We will move as fast as the least competent and least lucky elements of that mixture.”

The heart of the hell lay in the batteries, those electrochemical hearts pulsing at the factory’s core. “The primary production constraint really by quite far is in battery module assembly. So a little bit of a deep dive on that. There are four zones to module manufacturing that goes to four major production zones. The zones three and four are in good shape, zones one and two are not. Zone two in particular, we had a subcontractor, a systems integration subcontractor that unfortunately really dropped the ball, and we did not realize the degree to which the ball was dropped until quite recently, and this is a very complex manufacturing area. We had to rewrite all of the software from scratch, and redo many of the mechanical and electrical elements of zone two of module production. We’ve managed to rewrite what was about 20 to 30 man-years of software in four weeks, but there’s still a long way to go. Because the software working with the electromechanical elements need to be fabricated and installed and getting those atoms in place and rebuilt is unfortunately a lot longer and has far more external constraints than software. This is what I spent many late nights on the Gigafactory working on. JB has been here constantly and we reallocated many of our best engineers to fundamentally fixing zone two of the module line and then not far behind that is zone one.”

In these passages, Musk’s cadence quickens, a mix of exasperation and exhilaration—the subcontractor who “dropped the ball” a shorthand for human frailty in the face of atomic precision, the “20 to 30 man-years” of code reborn in four weeks a testament to Tesla’s internal alchemy. He confessed his own immersion: “And like I said, I am personally on that line in that machine transload problems personally where I can. And JB is basically spending his life at the Gigafactory.” It evoked Isaacson’s portrait of Musk as nocturnal alchemist, floor-bound and fevered, yet emerging with upgrades: “We also have a new design for zone one and two that is about three times more effective than the car design. So when we put in—and there are three lines of module production. Lines one, two and three are essentially identical. Line 4, which will be the new design, will be at triple the effectiveness of—will be as good as the other three lines combined. So we’re very confident about a future path of having incredibly efficient production of modules and that this will not be a constraint in the future but, unfortunately, it just takes some amount of time. This is like moving like lightning compared to what is normal in the automotive industry.”

Even the tempests of tabloid scrutiny, rumors in the press of mass firings, Musk dispatched with a prosecutor’s clarity, turning defense into doctrine that crackled with righteous fire. “The other thing I want to mention is there a lot of articles about Tesla firing employees, and layoffs and all the sort of stuff, these are really ridiculous. And any journalist who has written articles to this effect should be ashamed of themselves for lack of journalistic integrity. Every company in the world, there’s annual performance reviews. In our annual performance reviews, despite Tesla having an extremely high standard, a standard far higher than other car companies which we need to have in order to survive against much larger car companies… you can’t be a little guy and have equal levels of skill as the big guy. If you have two boxers of equal ability and one’s much smaller, the big guy’s going to crush the little guy, obviously. So little guy better have heck of a lot more skill and that is why [Tesla] is going to get clobbered. So that is why our standards are high. They’re not high because we believe in being mean to people. They’re high because if they’re not high, we will die. Despite that, in our annual performance reviews only 2% of people didn’t make the grade. So that’s about 700 people out of 33,000. This is a very low percentage… And then also it was not reported that several thousand employees were promoted and almost half those promotions were in manufacturing.”

This was Musk the meritocrat, unapologetic in his rigor, yet suffused with a fierce loyalty to the capable: promotions as the unsung counterpoint to severance, a rising tide lifting the skilled. As the call wore on, he sketched the ramp’s true geometry, not the skeptics’ straight line, but an S-curve of stealthy acceleration. “The ramp curve is a step exponential, so it means like as you alleviate a constraint, the production suddenly jumps to a much higher number. And so, although it looks a little staggered if you sort of zoom out, that production ramp is exponential with week over week increases… So it’s really an S-curve. It starts off really slow and then it ramps very rapidly on an exponential basis. It does start to go sort of linear right in the middle and then it sort of asymptotes off at the target production capacity… We’re highly confident of the long-term margin number of 25% or higher for Model 3.”

And then, in a moment of unguarded candor prompted by an analyst’s query, “Elon, you described Model 3, the Model 3 launch as production hell. I mean, you have a cold, but how hot is it in hell right now? And is it getting hotter or less hot? I mean are we solving more problems than are coming up?”—Musk replied with a weariness that pierced the ether: “I mean these…” The transcript trails there, a cliffhanger in the storm, but one senses the answer in his very presence: cooler, inch by inch, because Musk does not merely endure hell; he engineers its extinction. “It’s remarkable how much can be done by just beating up robots, shortening the path, intensifying the factory, adding additional robots at choke points and just making lines go really, really fast,” he had said earlier. “Speed is the ultimate weapon.”

In the years since, that weapon has propelled Tesla from Silicon Valley purgatory to orbital ambition – Cybertrucks prowling highways, Optimus glimpsed in prototypes, autonomy inching toward the regulatory horizon Musk once promised “with the current computing hardware.” Yet it is in these 2017 transcripts, amid the sniffles and the shadows, that one hears the purest strain of his obsession: not with glory, but with the grind that births it. Musk, the floor-sleeper turned frontier-pusher, reminds us that true prophets do not ascend thrones; they rise from the dust, quoting code and curves, their voices hoarse but unquenched. In an age of easy cynicisms, his is a summons to the possible – a call, from the front lines, to build faster, dream bolder, and never, ever lay down for good.